The London Classic Car Show 2023

Molly and I headed to Kensington Olympia this weekend for The London Classic Car Show for a fun-filled day of classic cars from up and

Molly and I headed to Kensington Olympia this weekend for The London Classic Car Show for a fun-filled day of classic cars from up and

Today, we delivered our 2008 Harley-Davidson 883 Sportster to lucky winner Sarah Janney. Sarah won this beautiful motorcycle in the live draw held on 9th

Classic car technician John has been working on getting our 1970 Bristol 411 running. A new air filter needed to be fitted, however, as the

Founded in 1945, the letters BRM would become synonymous with flying the British flag in the early years of Formula 1 and the following decade.

Work has continued on our 1970 Jensen Interceptor with classic car technician fitting new 90-degree terminals to the fans, in order to aid clearance of

Various parts of our 1959 Jensen 541R have been with classic car technician Mauro in the Bridge Classic Cars paintshop. The wheels of our rare

Our 1979 Austin Morris Mini 850 has been in the Bridge Classic Cars paintshop with classic car technician Mauro. Our classic Mini was rubbed down

Our 1960 Jensen 541R has stayed under the care of classic car technician Rob. Rob continued his work making and welding panels for the right-hand

Classic car technician Steve has been working on our 1958 AC Ace. Steve drained the diff, gearbox, and engine oils from this stunning classic car

Our 1964 Daimler 250 V8 has been going through a detailed assessment with classic car technician Scott. Scott has been checking the car to see

Molly takes you behind the scenes of the Bridge Classic Cars workshop and takes a closer look at some of our current projects.

Molly and I headed to Kensington Olympia this weekend for The London Classic Car Show for a fun-filled day of classic cars from up and down the country.

On arrival, we were greeted by the organisers who encouraged us to walk around and view all the exhibitions brought together by this event. One of the main attractions was an iconic display of Minis designed for members of the Beatles. A highly decorated one belonged to George Harrison and one had even been converted for Ringo Starr to be able to put his drums in the back!

The Aston Martin Club, Ferrari Owners Club and The Triumph TR Register Car Club amongst many others were there representing their clubs. And there was a great display of many cars, some over 100 years old.

Earlier in the weekend there had been an auction take place, hosted by Historics Auctioneers. A great many lots were available with some truly remarkable cars on offer.

Molly was lucky enough to be invited onto the Fighting Torque stage at 3 pm to talk about her thoughts on Barn Finds alongside Tobias Ballard, Nick Wells, and Vicki Butler-Henderson. She spoke to the audience about our 1905 Riley 9HP and our love for uncovering hidden treasures in unexpected places.

After finishing on stage, Molly and I bumped into Tobias as he headed back to his own stand, The Model A Revival Company. A few years ago he recreated his very own version of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang using car components from vehicles dating before the 1930s, Tobias gave us a quick run-through about where all of the parts were sourced from. There was even an incredible snake horn down one side! It is a very special vehicle and provokes feelings of nostalgia.

It was great to see so many special cars in one place, surrounded by the people that are the most passionate. We are looking forward to next year.

Today, we delivered our 2008 Harley-Davidson 883 Sportster to lucky winner Sarah Janney.

Sarah won this beautiful motorcycle in the live draw held on 9th February when her ticket number, 1246 was randomly selected.

Sarah’s husband accepted the delivery on her behalf and, as you can see from the photos below, the bike looks great in its new home.

Everyone here at Bridge Classic Cars would like to congratulate Sarah again on winning, and we hope she enjoys the latest addition to her garage.

Classic car technician John has been working on getting our 1970 Bristol 411 running.

A new air filter needed to be fitted, however, as the filter base plate has been modified, it fouled the throttle. To overcome this, John used the base plate from the original air filter and cut it down to the right size. He then drilled and located the breather elbow before painting the base plate black.

The modified base plate, breather connection, and filter were then all fitted and secured in the car.

John continues to work on our 1970 Bristol 411 and we are looking forward to progress continuing to be made on this beautiful classic car.

Founded in 1945, the letters BRM would become synonymous with flying the British flag in the early years of Formula 1 and the following decade.

British Racing Motors was founded by Raymond Mays (who was the man behind the brand ERA) and Peter Berthon – who after the war used the engineering know how from building hillclimb cars and their access to pre-war Mercedes and Auto Union designs to forge an alliance and build a brand that would literally have ”racing” in its name and enter Britain onto the world stage once more in top-flight racing.

The financing of the original plan was done through a series of industry connections and trusts. This would prove difficult in the long run for the fledgling company along with less than impressive results until one of its backers stepped up – the enigmatic Alfred Owen. Owen was the owner and chairman of the Rubery Owen Group, a group of companies responsible for manufacturing components for the automotive industry. With his expertise in organisation and management, Owen took over the running of British Racing Motors in the early 1950’s but Mays and Berthon would continue to run the team on Owen’s behalf well into the 1960s when the job was given to Owen’s brother-in-law Louis Stanley to run.

At the company’s HQ in Bourne, Lincolnshire they would created some of the greatest F1 cars of the 1960s utilising drivers such as Jo Bonnier, Graham Hill, Jackie Stewart, John Surtees, Niki Lauda, Clay Regazzoni and Tony Brooks to name but a few world class wheelmen on the driving duty roster for the team through its 20 year racing history.

Going back to 1954, the team would debut the car that would set them onto the world stage not only in Formula 1 but in the world of engineering with the Type 15, a design that that been developed since 1947.

The Type 15 would take advantage of the post-war rule change for engine sizes. The rule change stated that a car could have an engine size not in excess of 4.5-litres naturally aspirated but for any sort of forced induction the engine size would have to be 1.5 litres. Taking the latter approach, BRM created a masterpiece of technical skill and know-how. The team of Peter Berthon, Harry Mundy, Eric Richter and Frank May would take two 750cc V8’s and make a 1.5-litre V16… To get the power up to where the bigger naturally aspirated engines were BRM turned to the experts at Rolls Royce to build and develop a twin-stage centrifugal supercharger for the car. During its testing with Rolls Royce, to calibrate the superchargers, the small scale monster would rev out to over 12,000RPM with Rolls Royce engineers commenting that it still had more room to go if needed. During this, legendary engineer Tony Rudd would be brought into BRM from Rolls Royce to help with future engine development and eventually lead him to working with both BRM and Lotus after his aero-engine career.

This engineering tour de force would put the BRM name in-front of the automotive world. However, it proved to not be that reliable. In 1954, the regulations would change once more and essentially outlaw this beautiful engine.

Next, the team would develop the car which gave them their winning name and reputation. The Type 25.

The Type 25 would meet the new 2.5-litre regulations that came into effect in the mid-1950s. This would prove to be the beginning of BRM’s most successful period thanks to help from outside sources as well as a determined and highly talented team. The car was a slow and trying development for the team, but with the help of people such as Colin Chapman from Lotus along with drivers like Stirling Moss backed by the infamous Rob Walker (who combined the BRM engine into a Cooper Climax chassis to create a Cooper-BRM) to test out the strong and weak points of the design, the Type 25 (which would then be developed into the rear-engined P48) was developed and refined into formidable racing machines.

In 1962, BRM would win their first Formula 1 world championship with Graham Hill driving the formidable P57. To help pay for the racing programme, BRM would also become an engine supplier for privateer teams with the in-house designed and built V8. This would mark the beginning of the teams 2nd resurgence in F1 and its wild technical world.

In the mid-1960s, the team would embark on some of the grandest engineering projects to be undertaken by a British racing team, alongside the development of its own F1 projects like the fabled V12 and the doomed H16. In 1963, talks were in progress between the automotive might of Rover and the now well established BRM team to work together on a project outside of F1.

The meeting came about because of BRM’s owner, Alfred Owen. Owen was still the owner of Rubery Owen. The firm had been supplying Rover with automotive parts for decades at this point and with his connection in the BRM team, the board at Rover (mainly William Martin-Hurst, MD at Rover) decided it would be the perfect partnership to push both brands further into the motorsports world with a very unconventional engine and they would need the help of an established and well run team to be able to pull of this task.

Rover had been developing an engine since the end of the 2nd World War that even today, in 2023, is still seen as exotic and futuristic in a car. It was of course, the jet turbine. Rover initially debuted its revolutionary engine in the famous ‘Jet 1’ car in 1949/1950 but it didn’t end there. The team would go on to develop the T1, T2, T3 and T4. The T4 would actually be displayed at the 1962 24 hours of Le Mans before the race to do exhibition laps and prove the viability of this engineering project.

With the reception and experience gained in this publicity stunt, Rover decided it would enter a turbine powered car into the race the following year to prove the competitive nature of the turbine technology but also its endurance. So, Rover began the talks with BRM.

BRM would handle the development of the chassis and suspension for the car under the supervision and control of Tony Rudd. Using the damaged chassis from Richie Ginther’s 1962 Monaco Grand Prix F1 car, the team set about converting it into an open-top prototype for the team to develop the relevant systems and the set up of the car. The car was fitted with a single-speed transaxle (much like a modern electric car) and taken to the MIRA test track in April of 1963 to begin testing in the more than capable hands of Graham Hill. At the end of testing, Hill would describe the experience as ”You’re sitting in this thing that you might call a motor car and the next minute it sounds as if you’ve got a 707 just behind you, about to suck you up and devour you like an enormous monster.” One can only imagine the sounds and experience of the 150BHP jet turbine when it approached its top-speed during testing of just over 140mph.

With the proof of concept there for both BRM and Rover, the team could begin on the work for preparing the car for Le Mans in 1963.

The Rover-BRM would arrive at Le Mans in the summer of 1963 with Graham Hill and Richie Ginther given control of the car. The sanctioning body decided to allow the car twice the fuel of a conventional car and it ran with the designation of ’00’ to show it was experimental. The goal for the 1963 race was to develop and learn about the turbines use for extended periods and to take advantage of a prize for the first jet turbine to complete 2,600 miles in 24 hours while also achieving an average speed of 93mph, the car would go onto crush that challenge with hours to spare in the race. With the car being placed in the experimental class, it would not be given a technical finishing place. But, if it were conventionally powered the car would have placed 8th overall – a positive start to the Rover and BRM partnership.

Using everything they had learned in the 1963 race, the turbine engine went back to the Rover engineers for internal modifications to help with the efficiency in the form of a pair of ceramic rotary regenerators. These would be used as both heat exchangers for the car but also as a way of pre-heating the intake air temperatures. This would ultimately take away from the cars power for the race, but help its reported ferocious fuel consumption. Along with its mechanical update based on the ’63 race, the bodywork was redesigned by Rover engineer William Towns to be a closed cockpit style racer – helping with the cars aerodynamics. However on the way back from the pre-race tests early in the summer, the car was damaged and withdrawn from the race and the team busied themselves to build up the ultimate configuration for 1965.

For 1965, after proving itself as competitive and durable enough in 1963, the Rover-BRM would be allowed to run at full anger in competition against other cars in its 2-litre class. Because of this, the governing body said that the team would only be allowed the same fuel allowance as a normal piston driven car, making those ceramic rotary regenerators even more crucial to the teams success as it was now about efficiency rather than out and out speed for Graham Hill and Jackie Stewart charged with piloting the now enclosed prototype.

The story of that race goes that after running wide in a turn with Hill behind the wheel, the cars intakes inhaled dirt/sand which was sent directly into the turbine blades. Sand at that pressure and speed is highly-abrasive which had led to damage on the fan blades and ultimately the engine beginning to overheat – this would be near enough constantly monitored and nursed throughout the race by the BRM team. Later in the race, Jackie Stewart was inserted into the red corduroy lined cockpit of the car where the drama really began. Some say that due to the damage that began with the car inhaling the sand on the excursion off the track with Hill earlier in the race, a large piece of a fan blade fractured and was sent hurtling into the turbine and severely damaging one of the ceramic regenerators, noted by Stewart as a ”massive explosion” but thankfully and also mercifully, the turbine continued to run…

At the end of the 1965 running of the Le Mans 24 hours, the Rover-BRM partnership would cross the line 10th place overall and earn itself 2nd in class for the 2-litre formula. A very respectable position for any car let alone something that 2 years before had simply been an experiment between an automotive giant and a racing legend.

In 1974, the car was completely retired from any active service and has spent the last 49 years going between museums and static displays except in 2014, when for old times sake the turbine was fired up and the car taken around the legendary Circuit de le Sarthe to show it could still stun crowds.

After the 1965 race however, the Rover-BRM partnership would come to an end. Rover deciding that the turbine road car idea was still a distant dream with a lot of development work still required. BRM concentrated its efforts back onto Formula 1 (as well as other automotive projects) where it would remain, in its original guise or another, until 1977/1978 when the team effectively completely withdrew from top flight motorsport (until their recent resurgence under the leadership of Alfred Owen’s grandson, Simon). Rover however, would continue building passenger cars until 1967 when it was bought out by British Leyland. The Rover name as we would know it would continue on until 2005 with the closure of British Leyland.

In 1997, to commemorate this herculean project between the two companies, the Rover and BRM name would reappear on a limited edition hot hatch. The Rover 200 BRM. This was built to celebrate significant aspects of both companies heritage and their joint project of the mid-1960s. The Brooklands Green paintwork, the striking and contrasting orange front grille surround and the brushed aluminium accents that adorn this underrated 1990s hot-hatch.

And now, Bridge Classic Cars is giving you the chance to win one of these rare and unique cars that celebrate the union between an automotive powerhouse and a racing legend. Click here to to get your tickets and be in with a chance of winning our 1999 Rover 200 BRM.

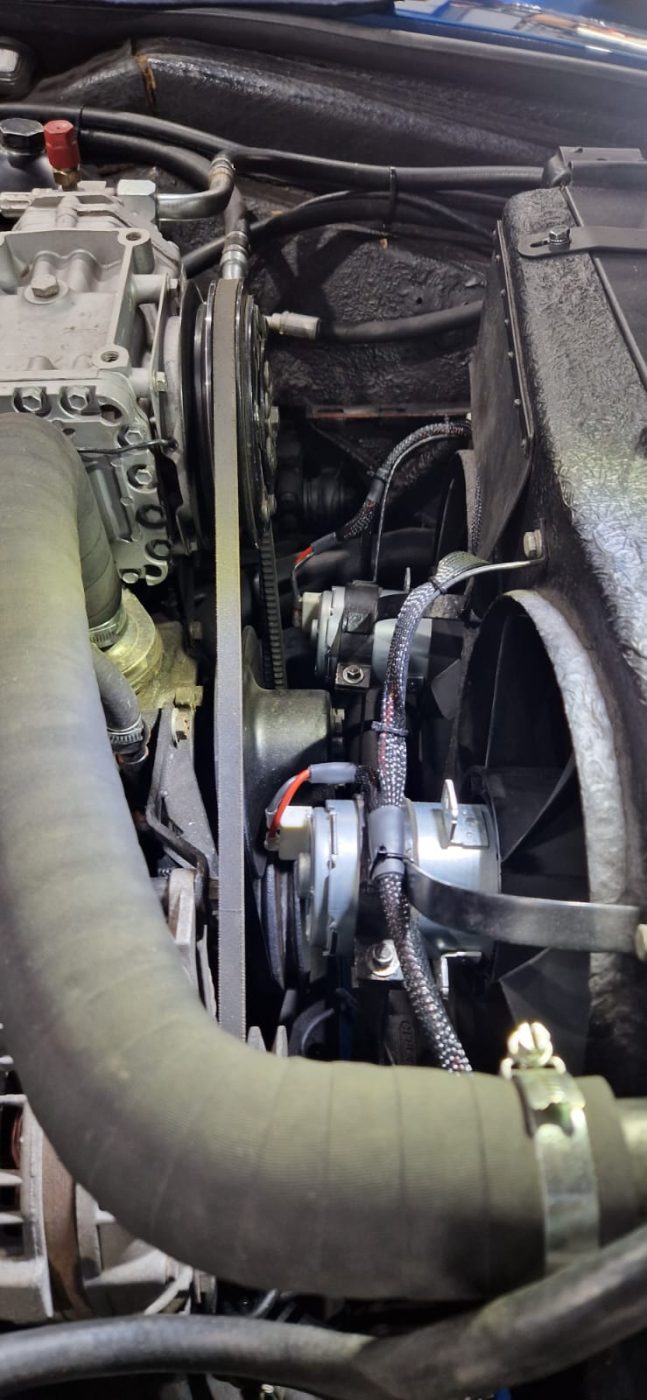

Work has continued on our 1970 Jensen Interceptor with classic car technician fitting new 90-degree terminals to the fans, in order to aid clearance of the auxiliary belt. Once this was complete, John took the car outside to run it up to temperature before test-driving it.

When the car was up to temperature, the idle speed was adjusted. The fans now cut in and out as they should and the oil pressure was good with no stalling happening now, as it had been reported by the car’s owner.

With John continuing his work on our 1970 Jensen Interceptor, it won’t be much longer until it can be returned to its owner to get it back out on the road.

Various parts of our 1959 Jensen 541R have been with classic car technician Mauro in the Bridge Classic Cars paintshop.

The wheels of our rare Jensen have been primed while other components have been painted black.

Now that the chassis has been painted, with the addition of these newly painted parts, progress continues to be made on our 1959 Jensen 541R.

Our 1979 Austin Morris Mini 850 has been in the Bridge Classic Cars paintshop with classic car technician Mauro.

Our classic Mini was rubbed down and had primer applied in preparation for it to be painted very soon.

It won’t be too much longer before our 1979 Austin Morris Mini 850 is fully painted and, eventually, it will go on to be a competition car through Bridge Classic Cars Competitions.

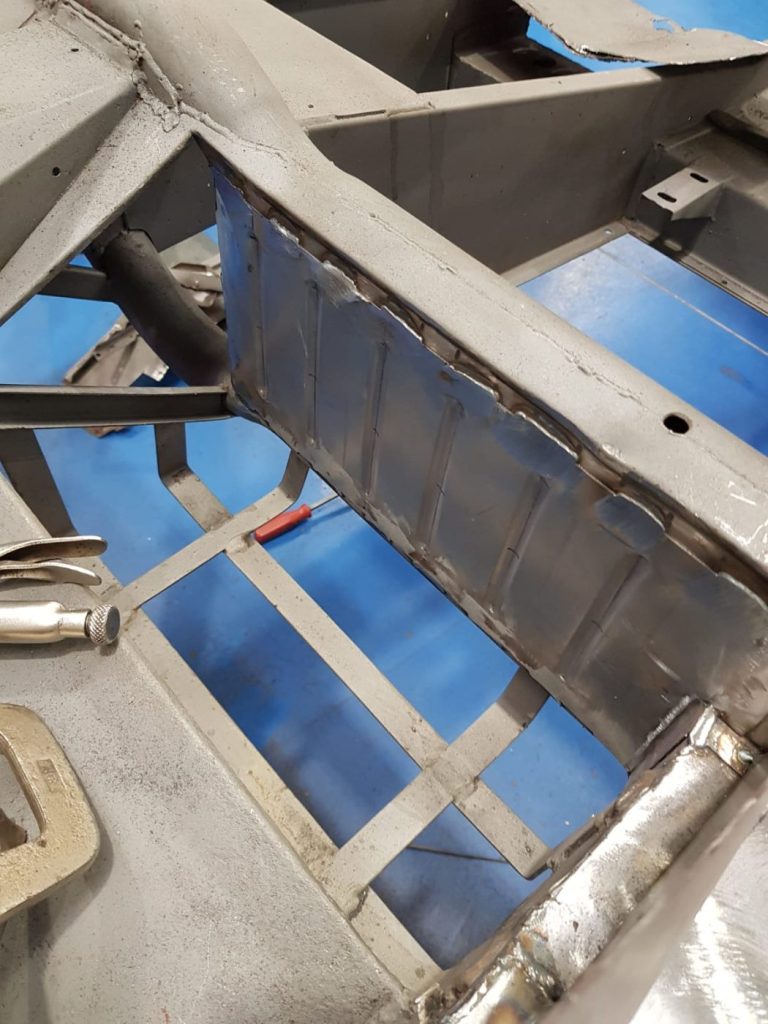

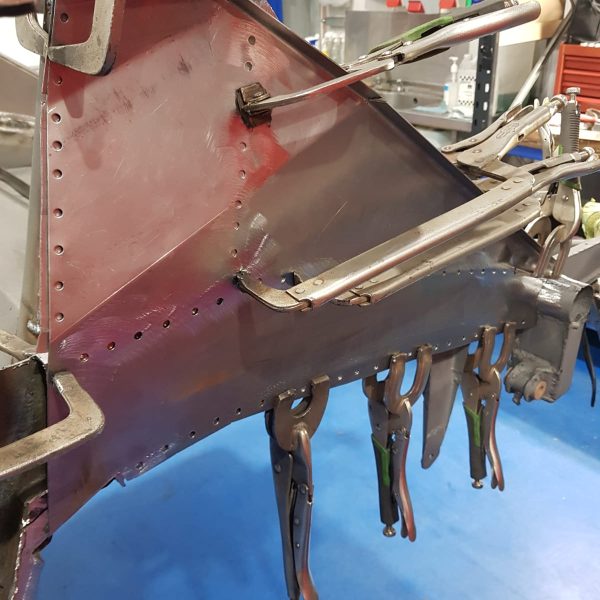

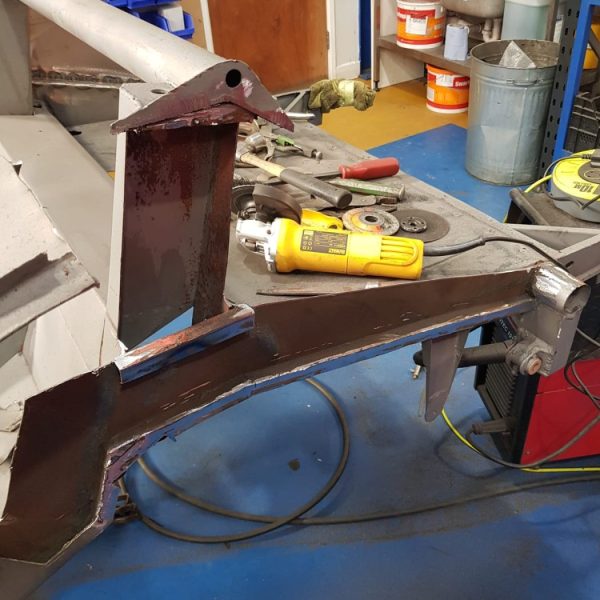

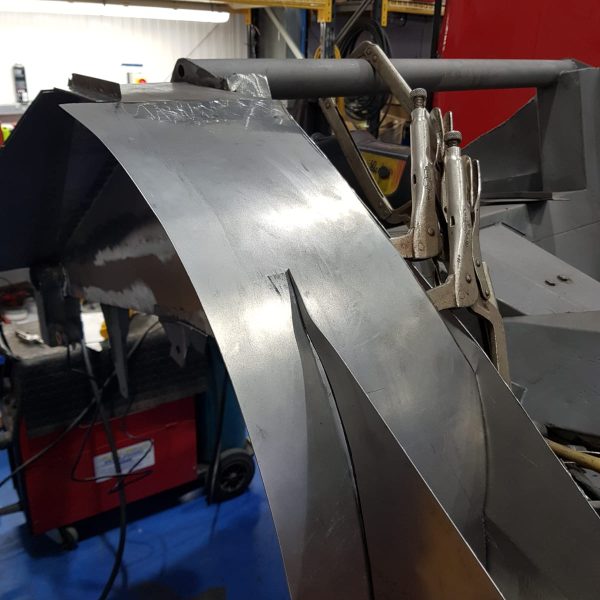

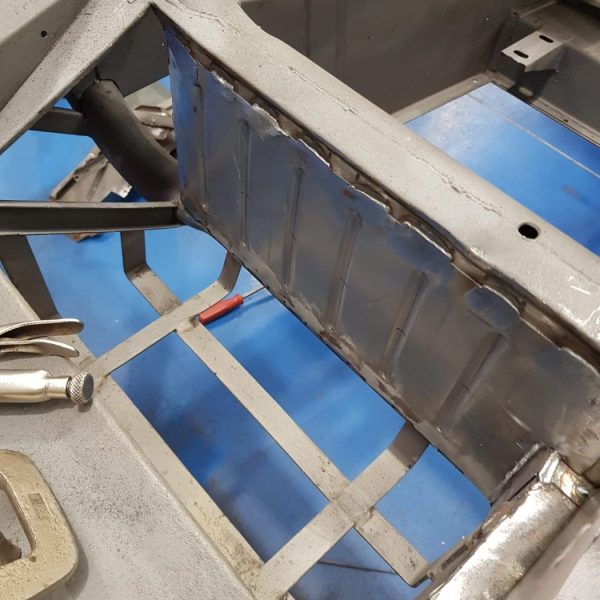

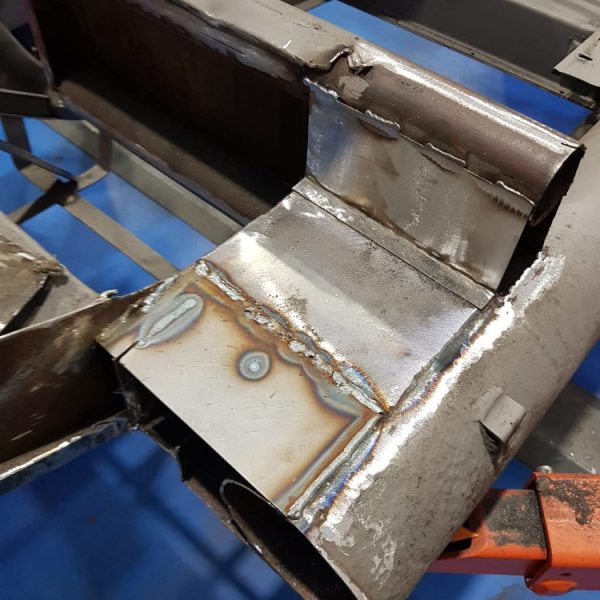

Our 1960 Jensen 541R has stayed under the care of classic car technician Rob.

Rob continued his work making and welding panels for the right-hand rear wheel arch. Once this was finished, he began the process all over again on the left-hand side of the chassis. This involved more cutting and welding.

Like the right-hand side rear wheel arch, the left-hand side also needed to be fabricated and welded into place.

The chassis of our 1960 Jensen 541R is still undergoing work and, with more repairs needed, it is likely to stay with Rob for a bit longer before its able to move on with its restoration.

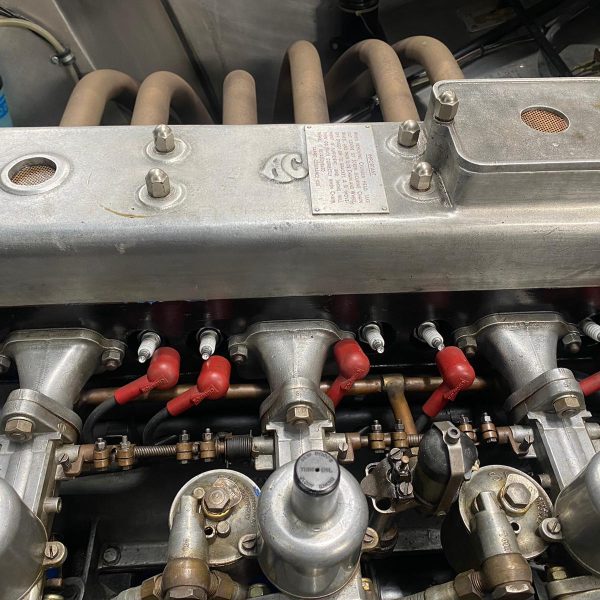

Classic car technician Steve has been working on our 1958 AC Ace.

Steve drained the diff, gearbox, and engine oils from this stunning classic car before moving on to replacing the spark plugs.

To fill the gearbox, Steve used the access cover on the transmission tunnel. After doing this, he also removed the washer pump in order to unblock the pipes.

Our 1958 AC Ace is a very special classic car and work continues to make sure it stays in the same great condition in the future.

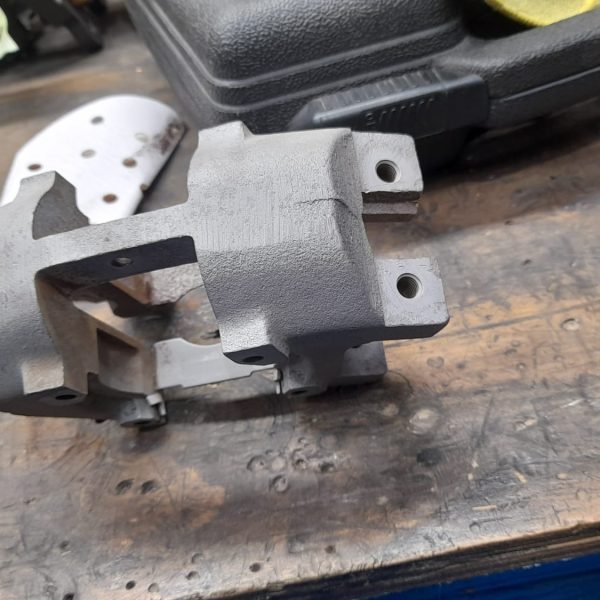

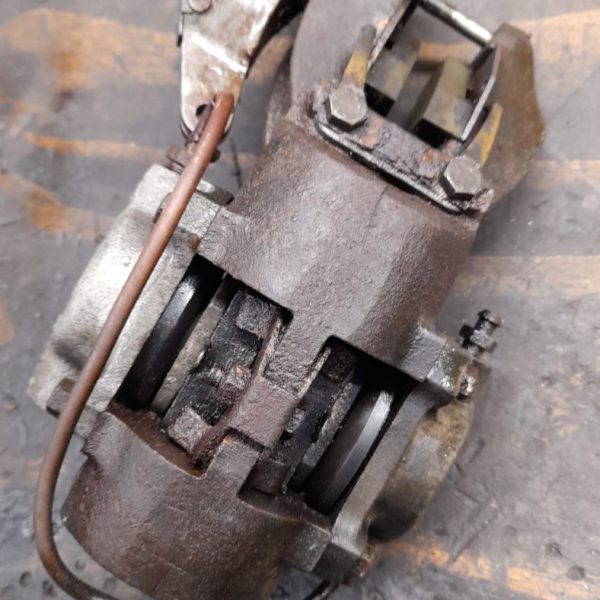

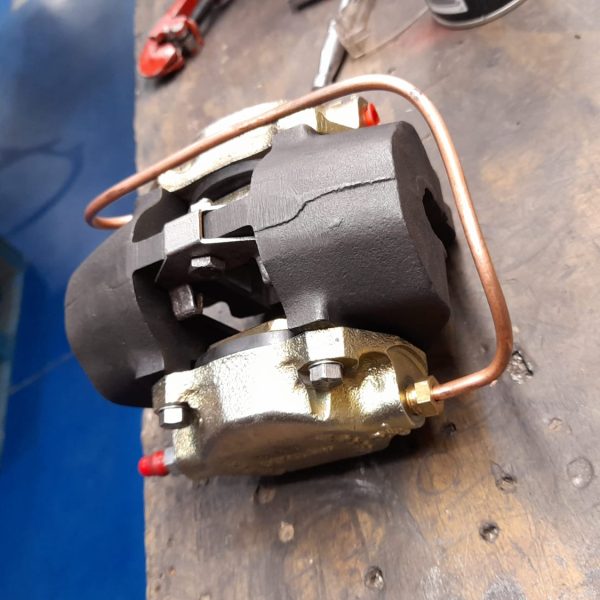

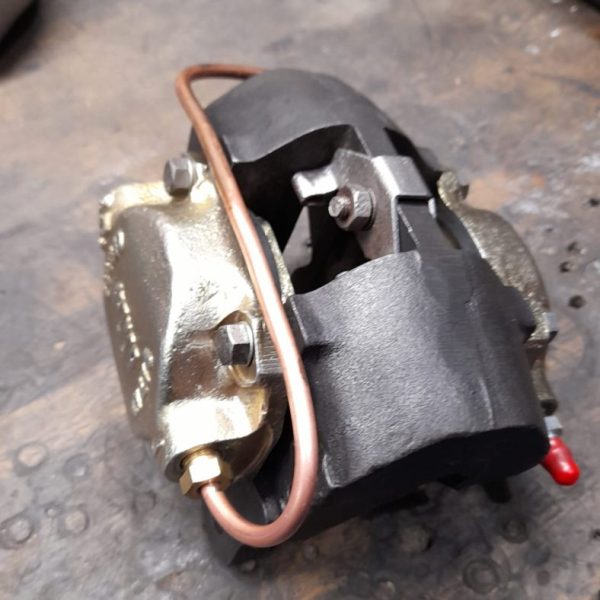

Our 1964 Daimler 250 V8 has been going through a detailed assessment with classic car technician Scott.

Scott has been checking the car to see what work and parts will be required to get it back out on the road. His initial findings suggest that most of the brakes and rubber components need to be replaced.

The next step of Scott’s assessment involved checking and cleaning the fuel system. He removed the old tank and checked the electrics. While doing this, Scott found that the pump wasn’t working so he has replaced this with a temporary one for now.

Scott went on to check the oil and make sure that there were no obstructions in the intake. He was actually able to get the car running before he stripped and rebuilt the brake calipers.

Once the car was running, Scott moved our Daimler to the wash bay. After removing the wheels, he steam-cleaned the underside of all of the old thick grease and grime.

The rear axle was removed, stripped, and cleaned and the rear bushings were removed too. The rear springs were also removed and cleaned.

After Scott had finished his assessment, classic car technician Mauro painted the rear diff and propshaft of our 1964 Daimler 250 V8.

Molly takes you behind the scenes of the Bridge Classic Cars workshop and takes a closer look at some of our current projects.

Bridge Classic Cars are award winning Classic Car Restoration and Maintenance specialists. Your pride and joy is in safe hands with our expert Classic Car Technicians. Take a look at our awards here.